The latest issue of The EastAfrican leads with a story headlined “Under Siege”, describing how opposition politicians in Tanzania, Uganda and South Sudan face severe repression as elections approach.

In Tanzania, Chadema party leader Tundu Lissu was charged with treason and detained indefinitely for his “No Reforms, No Election” campaign, aimed at stalling the October elections, which the party claims would be rigged in favour of the ruling CCM without electoral reforms. Chadema was subsequently barred from the vote, ostensibly because it failed to sign a mandatory code of conduct by the deadline set by the Independent National Electoral Commission. Critics claim the disqualification was a tactic to suppress opposition.

In Uganda, opposition leader Dr Kizza Besigye, a long-time rival of President Yoweri Museveni, is detained on treason charges, denied bail, and faces trial in a military court despite a civilian court ruling. Dr Besigye was abducted in Nairobi by Ugandan security operatives and spirited back home on 16 November, 2024.

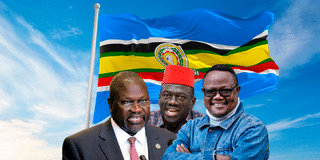

South Sudan’s First Vice President Riek Machar (left) Uganda’s opposition leader Dr Kizza Besigye, and Tanzania’s Chadema party leader Tundu Lissu.

Photo credit: Nation Media Group

Civil-war

In South Sudan, Riek Machar of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In-Opposition, who holds the position of First Vice President as part of a national unity arrangement to end a bloody war, is under house arrest. His party has splintered, and his role as First Vice President is threatened amid tensions with President Salva Kiir.

South Sudan, the world’s newest nation, became independent from Sudan as a woefully underdeveloped and poor region on July 9, 2011. Because of this, some are willing to give it a pass. Not so Tanzania and Uganda—especially Tanzania, which, unlike the previously civil-war-plagued Uganda, has had relative stability for over 60 years. The latter two should perhaps be embarrassed to be in the same nasty political salad bowl as South Sudan. They should be playing in the same league as their neighbour Kenya.

Kenya’s democracy, while flawed in many respects, still outperforms Uganda’s and Tanzania’s by far. Data from Freedom House (2024) ranks Kenya as “partly free” (score: 52/100), Tanzania as “partly free” (40/100), and Uganda as “not free” (34/100).

For all its imperfections, it is now inconceivable that a Kenyan president could imprison a rival ahead of a vote to keep him or her off the ballot. For 30 years now, even when polls have been marred by violence, no Kenyan opposition leader has been arrested in a disputed election contest.

Someone summed it up this way: Kenyan elections are contentious but competitive. While fraud and violence occur, mechanisms like judicial review improve credibility. Uganda’s elections are neither free nor fair, with widespread rigging, voter intimidation and security force interference. The electoral commission is seen as a ruling party tool. In Tanzania, elections favour the ruling CCM, with skewed voter registration and restricted campaign spaces.

Executive power

These differences have been attributed to various factors. The 2010 Constitution devolved power to 47 counties, reducing central control and enabling local governance. It strengthened institutions like the Judiciary and electoral commission, providing checks on Executive power. Regular, competitive elections, though imperfect, are underpinned by constitutional safeguards.

Uganda’s 1995 Constitution centralised power in the presidency. Museveni’s 39-year rule, enabled by constitutional amendments removing term limits, stifles opposition. Like Uganda’s, Tanzania’s 1977 Constitution concentrates power in the Executive, with limited checks from the Judiciary or Legislature. Additionally, CCM’s unbroken rule since independence—the longest continuously ruling political party in Africa—creates a de facto one-party State.

Furthermore, the Judiciary in Kenya has demonstrated sporadic independence, notably annulling the 2017 presidential election due to irregularities. Uganda’s courts are mostly subordinate to the Executive, with judges often pressured in political cases.

In Tanzania, courts rarely challenge the ruling party, and political cases are resolved in favour of the state. Here, Uganda does better because you can challenge the outcome of a presidential election in court. In Tanzania, Article 41(7) of the constitution prohibits courts from entertaining a challenge to the election of a presidential candidate once the electoral commission declares a winner.

Unlike its peers, it is also reckoned that in Kenya, a freer press and active civil society hold leaders accountable, despite occasional clampdowns. Increasingly, two things seen as big problems for Kenya’s democracy—corruption and tribalism—are now being viewed as having an accidental “good” side. Ethnic rivalry, while divisive, prevents single-group dominance and limits the power of the Executive.

Kenya’s history of tribal coalitions fosters a culture of political negotiation. In other words, there is a path for the Kenyan opposition, even after it has been cheated at the ballot: loud protest, followed by a handshake and a hand-cheque. Put another way, Kenyans have been doing tribal politics for so long, that they have become very good at it and able to extract some good outcomes from the morass.

The author is a journalist, writer, and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. X@cobbo3.