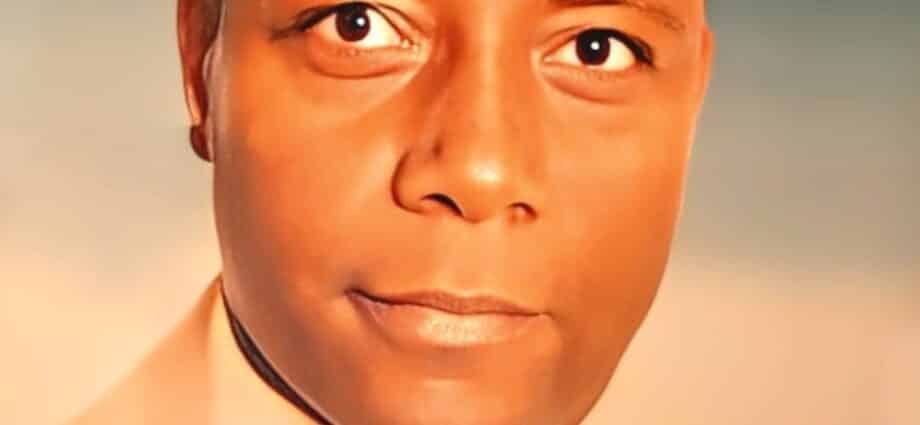

Freddy Macha

The late iconic journalist Ferdinand Ruhinda was not only a respectable leader and manager but also a true reflection of what Tanzanians have produced during the last 60 years or so.

Ruhinda not only scaled the diplomatic ladder n Sweden, Canada and China, but also sat in the upper echelons and offices in the media in Tanzania as he created newspapers and radio stations. All institutions he worked with and led are still breathing and functioning to this day.

That, in itself, speaks volumes.

In every profession across the planet we have individuals who bring something unique to that particular area. They do not just go through the motions – turning up at work, going home, returning the next day and retiring to their beloved families and enjoying their sunset years with a pension, grandchildren and backyard gardens.

They brighten up the place, pushing it up through their contribution. Such individuals, however, tend to be a few, unselfish visionaries.

As a young reporter, I never worked with Ferdinand Ruhinda directly because when I joined Uhuru na Mzalendo newspapers in 1976, he had just left for higher missions.

But I had interacted with him while I was still in high school at Mzumbe in Morogoro. Note this. As a prolific teenage writer, I was sending letters and articles while still an A level student. Ruhinda not only made sure that they were published, he sought one of my teachers, Nizar Visram (currently still writing and active), promising him to “employ this young boy as soon as he completes school”.

Can you imagine what goes on in a young person’s mind when offered such a glowing future while still crawling like a baby? How many get such an opportunity while still in their diapers (or living with their parents) and with no life experience whatsoever? And who trusts and believes that such an unknown novice shall deliver? Which leader and administrator takes such risks?

But Ruhinda could see talent and was keen and ready to nourish it! Like a leopard (or a lion) in the bushes of skills, he could smell and sense that here was potential.

Picture this. Tanzania had celebrated ten years of independence in 1971 and shortly afterwards I began sending articles and letters to major newspapers. One of my classmates at Ilboru Secondary School in Arusha, Rashid Othman (who decades later held a high position in the government), had won a national poetry competition that championed the Ten Years of Uhuru tag. Still a teenager, Othman was then invited to the State House and personally presented with his prize by none other than Mwalimu Julius Nyerere himself, then President of the United Republic of Tanzania.

There was an air of encouragement and self-belief across Bongo through an inspiration called the Tanzania Youth League, but not every leader gave opportunities to the youth, though. Some demonised us vijana as wahuni or useless rebels.

As soon as I finished my one year’s National Service stint at Mafinga, I joined staff at Uhuru na Mzalendo at Pugu Road (today Nyerere Road), Dar es Salaam, where I rubbed shoulders with a team of seasoned journalists.

Some, including Ndimara Tegambwage and Salva Rweyemamu, are still alive. Some, such as Omar Bawazir (who helped me learn how to ride a motorbike provided by the Uhuru na Mzalendo management), are gone. There were also Abdi Mushi (a brilliant Radio Tanzania presenter) and photographer Khatibu Ally.

Under Costa Kumalija, who had succeeded Ruhinda as managing editor, were other eager cub reporters such as Harrison Mwakyembe and Palamagamba Kabudi, who went on to become respected academics and later serve as Cabinet ministers, Awadh Shebe (the late Kariakoo-based photographer who I worked with very well ), the late Sengondo Mvungi and the late Yahya Buzaragi (ex-Mzumbe classmates), plus. Yes, we all flourished in that Pugu Road newsroom.

From then on, I would fly through the media, ending up as a columnist for the Sunday News in 1981 when I met another visionary editor, Ulli Mwambulukutu. Ulli, like Ruhinda, was unselfish and offered me a chance, which I promptly grabbed.

This is the lesson.

Non-egoistic leaders and professionals share their vision with those starting out and wishing to grow. They encourage and open doors. As such, communities thrive and prosper because of fresh, new talent. There is no need for bribes, fraud or backbiting.

How many times have we seen people in positions of authority give space to personal friends or family members who never delivered?

Herein then lies my tribute to a man who believed in talent and made me what I am today. Much has been said about Ferdinand Ruhinda.

Some might have different opinions, but my testament is genuine gratitude to a true national hero.

Freddy Macha is a Tanzanian journalist, artiste and author based in London. [email protected]