As the world reels from one natural disaster to another, Nigeria is among countries that experienced the brunt of devastating floods–some of the worst in decades. More than 600 people have died in the past few weeks alone, while 1.3 million have been displaced.

This stands in stark contrast to the situation in Kenya, where I spent the last three years working to advance women’s rights across Africa. In these communities, successive droughts have destroyed crops, wiped out community gardens, and deepened the hunger crises.

These variations across our continent align with what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has laid out in its sixth assessment report, which includes a dedicated chapter on weather extremes for the first time. Such climate-induced impacts are no longer a future prediction. We are witnessing them daily in our own backyards.

This is why I’m representing a coalition of African women and girls at this year’s climate negotiations (COP27) – deemed “the African COP” – taking place in Egypt from 6-18 November. These two weeks offer an opportunity to put climate justice for our continent at the centre by addressing the specific needs of communities most affected by environmental crises.

While all are experiencing the impacts of climate change, women and girls—whom the United Nations estimate make up 80 percent of all climate refugees—are among those hardest hit. In my own work, I’ve seen girls miss classes or drop out of school altogether when they are forced to walk an additional 30 minutes to an hour to fetch water, or firewood. I have seen women denied compensation because land they tilled is not on their names, and women left to support their families alone in the middle of a crisis. Such economic and non-economic losses caused by climate emergencies are experienced differently by women and girls.

For years, dedicated funding for this kind of “loss and damage”—climate impacts that can no longer be adapted to—has risen to the top of political agendas, only to be blocked by wealthy countries. It is clear that those who are driving global warming and destroying ecosystems and cultures are still comfortable with reaping the profits while communities, and particularly African women and girls, lose our lives and livelihoods.

As African feminists, we join civil society voices and member states in calling for a standalone, grant-based financing mechanism for loss and damage. At the same time, we know that no amount of climate finance will yield transformative change without centering justice and equity at all stages. We are seeing governments – for example, in Senegal – take steps to mainstream gender in the budgets of all ministries at the state level. And we are seeing new funding mechanisms that deliver resources to the community level, so community organizations can set their own agendas. Taken together, such efforts can subvert the charity models that are known to trap countries in cycles of debt or consolidate wealth in the hands of few, while transferring more resources to women and communities on the frontline of this work.

Perhaps most importantly, no efforts toward sustainable climate action will be possible without greater and more diverse representation of frontline communities in all spaces where climate financing decisions are made. As African women and girls, our lives are uniquely tied to the environment. Patriarchal systems, cultures and norms have made us women the ones who work the lands, fetch water, tend to family health, who largely stay when men migrate. While we are working in regions that are some of the most affected by climate change, we are also modelling feminist approaches that centre the wellbeing of both people and nature. And we’re pioneering solutions to adapt to a warming world. Yet, we are too often locked out of decision making spaces, while our ideas go under-resourced and overlooked.

While the negotiations under the UNFCCC have introduced a Gender Action Plan, little progress has been made in ensuring gender is fully integrated into all approaches and responses, including at the negotiating table. Between visa denials, language and translation issues, inadequate resources to attend global conferences, and inattention to our priorities—our ability to detail our experiences or contribute our knowledge in the style and formats required in global policy spaces like the UN climate talks is severely limited. In these multilateral arenas that already have notoriously limited and shrinking space for civil society, African women and girls continue to struggle to be heard.

Beyond providing more money for climate change adaptation, mitigation, and loss and damage, climate finance needs to resource a shift in our processes themselves—starting with more meaningful inclusion.

It’s time to remind world leaders that there is no solving the climate crisis without climate and gender justice—and justice demands that those who are at the margins be central to creating and benefitting from the solutions.

Share this news

This Year’s Most Read News Stories

Muslims in Pemba conduct special prayer against ZAA decision

ZANZIBAR: More than 200 Muslims in Vitongoji Village, South Pemba Region over the weekend conducted a special prayer to condemn the Zanzibar Airports Authority (ZAA) move to appoint DNATA as the sole ground handler in Terminal III of the International Airport of Zanzibar. Abeid Amani Karume.Continue Reading

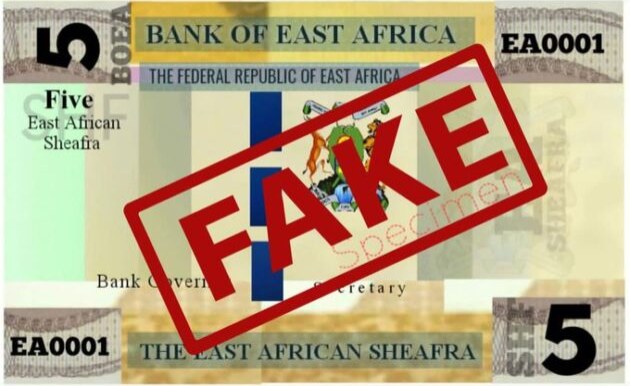

East African Community Bloc Dismisses Fake Common Currency

The secretariat of the East African Community (EAC) regional bloc has dismissed a post on X, formerly Twitter, which claimed that the bloc’s member countries have launched a common regional currency.Continue Reading

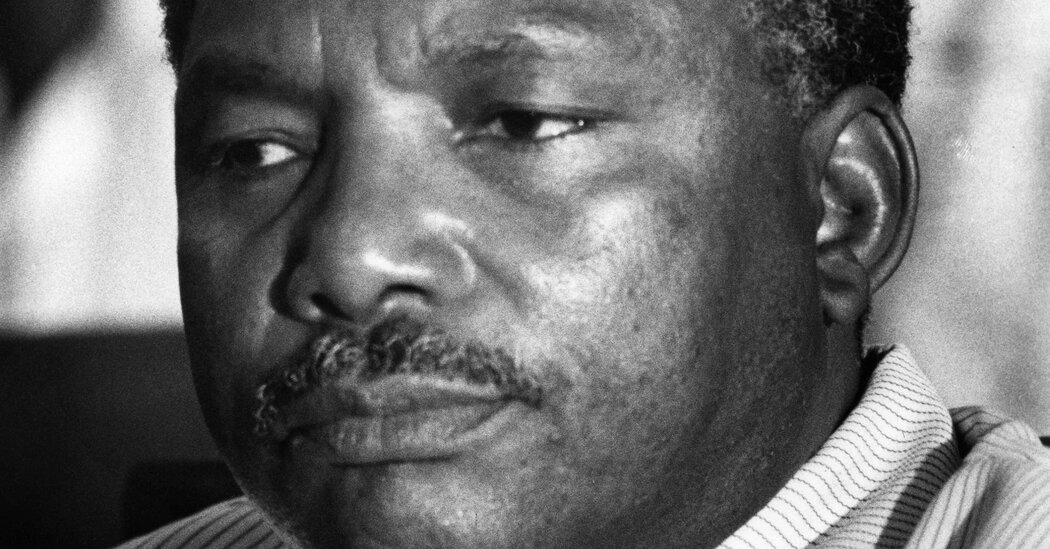

Ali Hassan Mwinyi, Former President of Tanzania, Dies at 98

Ali Hassan Mwinyi, a schoolteacher turned politician who led Tanzania as its second post-independence president and helped dismantle the doctrinaire socialism of his predecessor, Julius K. Nyerere, died on Thursday in Dar es Salaam, the country’s former capital. He was 98.Continue Reading