One of the most significant development challenges in Tanzania is the tendency to keep doing the same things over and over often at the expense of exploring more beneficial alternatives. Even when what we are doing has some utility, failure to expand our horizons by exploring new opportunities has needlessly limited our development potential. We need to break free from these ‘yale yale’ (business as usual)tendencies.

In previous articles about migration, I highlighted that this is one of those ‘billion-dollar’ opportunities that appears to be poorly utilised in Tanzania. Properly harnessed, migration could contribute up to 10 percent of the national GDP. However, our ad hoc approach to migration has hindered our ability to capitalise on this opportunity. We don’t know what we want and are consequently entangled in contradictions in our practices.

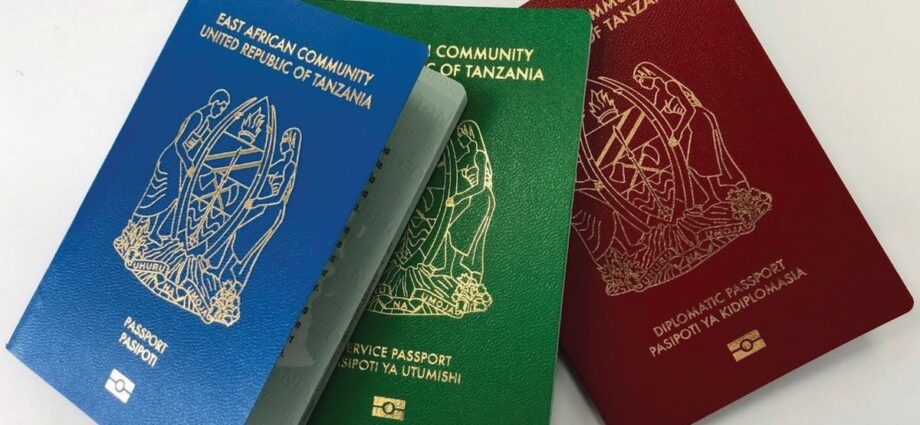

A clear example of these inconsistencies is our approach to issuing passports. On one hand, we claim that passports are the right of every citizen. However, when people apply for passports, the questions they must answer and the process they endure tell a different story.

For instance, one of the questions asked is, “Why do you need a passport?” If it’s a citizen’s right to have a passport, why should they justify their need for it? Isn’t it obvious why people need passports? Even if a specific answer is required, the question is redundant, as a passport can be used for multiple purposes once issued.

Moreover, one of the requirements for obtaining a passport is a National ID number. This requirement is sensible: NIDA serves as the primary identifier for all citizens, and possessing this identification implies that one’s citizenship has been conclusively established. Yet, alas, applicants are still subjected to additional document requirements, such as birth certificates, local government letters, and affidavits as if they need to prove their citizenship all over again.

Again, we don’t know what we want. We need to change our mindsets. Instead of making it as easy as possible to get a passport, which is the right of citizens anyway, we introduce complexities where none should be. As a result, we struggle to unlock the immense potential of migration for Tanzania’s economic development.

Kenya provides a valuable example. They have made significant strides in passport issuance, with over 5 million out of Kenya’s estimated 56 million population holding valid passports. Kenya now aims to have 10 million passport holders by 2028. Their efficient processes and technology have enabled them to produce over 10,000 passports daily, twice the current daily demand. As a result, Kenya boasts a substantial diaspora of about 3 million contributing significantly to the country’s economy through remittances and other benefits.

While Kenya benefits greatly from the purposeful management of migration matters, in Tanzania the trends are not flattering at all. By April 2021, the number of passport holders in Tanzania was less than 1 million and the number of Tanzanians abroad was less than 400,000, growing from 220,000 in 2000. If those trends remain true, 10 Kenyans emigrate for every Tanzanian. These are some of the facts that inform my opinion that Tanzania is not going to catch up with Kenya any time soon, despite Tanzania’s significantly superior comparative advantages.

The expansion of passport issuance has many direct and indirect benefits. To the immigration office, increasing the number of passport holders by 1 million would raise 150 billion shillings as direct fees. Applicants will also spend possibly another 50 billion in the process, creating more employment and stimulating economic activities. These developments would position the immigration office quite well, given that it is already one of the top three revenue earners for the government according to some sources, alongside TPA and TRA.

But more strategically, holding a passport empowers citizens to exercise their rights, expand their horizons, and pursue opportunities beyond their national borders. It enables individuals to travel, seek economic advancement, pursue education, reunite with loved ones, and receive diplomatic protection. Passports are also essential in emergencies, allowing citizens to evacuate or seek assistance.

We must significantly expand passport issuance. The immigration office needs to look at every citizen who doesn’t have a passport but can afford one as a potential client. They should be proactive. For example, with approximately 5 percent of Tanzanians holding tertiary-level education, equating to over 3 million people, ensuring that this group has passports would empower them to compete globally while generating hundreds of billions of shillings in revenue.

There are countries which have made possessing a passport mandatory. I understand that Ethiopia is one of them. While I may not go as far as advocating for making passport possession a legal requirement, we can at least start by making it an expected norm.

Ultimately, it is all about unlocking economic opportunities. The world is full of them. We have to embrace progress by abandoning our ‘same old, same old’ practices.