Upon being expelled from Tanganyika, Field Marshal John Okello was taken to Dar es Salaam airport amid heavy escort by Tanganyikan police. Accompanied by the country’s Minister of External Affairs Oscar Kambona, Okello sat in the tourist class while Kambona sat in the first class.

At Nairobi airport, they were met by then Kenyan Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s Office, Joseph Murumbi, who took Okello to the VIP Lounge.

Okello says in his book Revolution in Zanzibar that the following morning, he looked for Murumbi but was unable to locate him.

When he returned to his hotel, he found his luggage removed from his room and was informed that minister Murumbi had instructed that he would only be able to remain in the hotel if he was ready to assume charges himself.

“This was an extraordinary turn of events. I had neither money nor shelter,” Okello writes. He says he sat on the veranda shivering with fever and at lunch time, he was unable to eat because he did not have enough money.

He recalls that at 1:30pm, he met a European man who listened quite sympathetically to his story, then bought him lunch and gave him Shs100.

Later that afternoon, he decided to contact Murumbi at his office, but before he could reach there, Okello was met by the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Internal Security and Defence, JK Arap Kotie, who handed him a letter that read in part:

“Sir, I am directed by the minister of state in the Prime Minister’s Office [Murumbi] to inform you that the prime minister has directed that you are allowed to remain in Nairobi only today and during your stay, you are not to hold any press conference or any other public meetings. I am to add that you shall be required to leave the country by the first plane tomorrow morning, Saturday, March 14, 1964.”

Okello says his question to Kotie was: “How do you expect me to leave on the morning plane? How am I to pay the fare?”

“That’s up to you,” Kotie replied. “What the government wants is that you leave by the first available plane.”

“I looked at the heavens but found them too distant to reach. I looked at the earth but found it too heavy to carry. My situation was difficult for I had already spent some of the Shs100 that the good European had given to me,” Okello writes.

He says as he walked back to his hotel, he realised he had lost faith in the East African governments and could not expect assistance from any. On March 14, 1964, Okello left Nairobi for Uganda by road.

Inside Uganda

Upon reaching Uganda, he hoped that the Ugandan government would help him find some sort of employment appropriate to him. He was accommodated at a hotel in Kampala at the government expense and was assisted to reach his home in Lango District.

After a few days, he returned to Kampala and went to then Minister of External Affairs, Felix Onama, who told him that he was taking his question of employment to the higher authorities. Okello also asked the minister to contact the Zanzibar government to dispatch his personal belongings. Okello also saw Ugandan Prime Minister Milton Obote over the same matter. However, that was as far as it went. Nothing ever came out of it.

Life in Kampala

Life soon became extremely difficult for the former Zanzibar revolution icon, for he had no money and no possessions, and was unable to get employment in any public or private company. It soon became impossible for him to remain in Kampala in search of employment, for he could not pay the bills.

Okello notes that his final disillusionment came when the owner of the hotel where he was staying threw him out and confiscated the few belongings he had as payment for the unpaid bills, prompting him to start sleeping on the streets.

At this point, Okello says he thought it might be helpful to contact several African countries which had had their independence. He then wrote letters to and visited the embassies of Ghana and Nigeria but says the pittances he received would hardly cover his road fare to his home in Lango.

He then began to move to residential places of Asians and Europeans in Kampala and with good luck, he found an Asian who gave him Shs500. And another man from his own tribe gave him some money to obtain food from time to time.

At the same time, he notes some Ugandan ministers, Members of Parliament and government officials started to press him for information about Zanzibar and his own plans.

Realising that these people could be trying to dupe him into saying something they could report to the higher authorities, he decided to leave Uganda.

On September 27, 1964, Okello left Kampala for Nairobi where he met two Congolese nationalists who agreed to take him through Congo to join the war against Portuguese imperialists in Angola. As they drove via Mwanza in Tanzania en route to Congo, they were intercepted by the Tanzanian police who arrested them.

After days of detention, they were deported to the Kenyan border from where he returned to Uganda. After a failed mission to Angola, Okello retired to his home village in Alebtong and joined a peasantry life and lived there until 1971 when Gen Idi Amin overthrew Obote in a military coup.

Okello and Amin

By 1971 when Amin captured power, Okello had settled in his village in Lango. According to Bosco Opin, who added a second part to Okello’s book Revolution in Zanzibar, Amin’s coming to power was an entry of a hungry lion into a sheep pen.

Upon capturing power, there were killings of soldiers, politicians and prominent people mainly from Langi and Acholi tribes. As a result, countless people fled the country. Okello could have fled, but the question is how and where given the restriction not only in Uganda but also the neighbouring countries had placed on him.

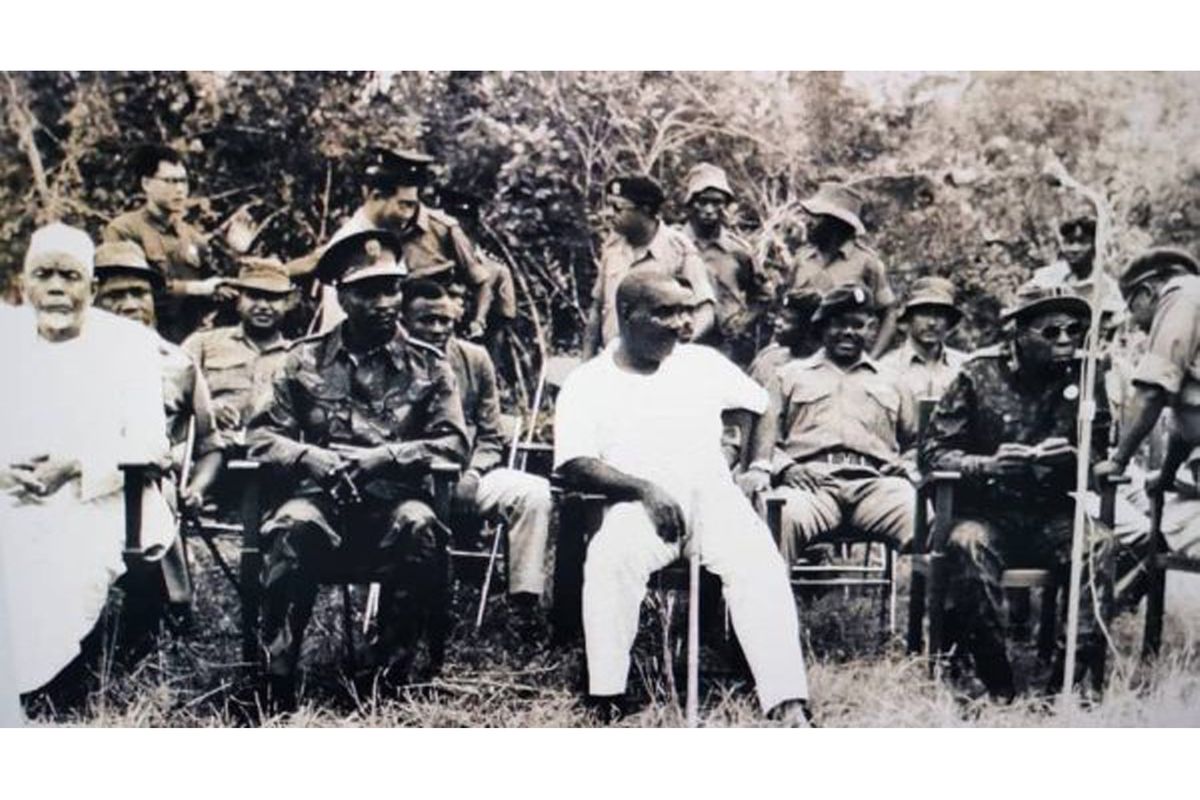

Opio notes that at first, Amin extended a hand of friendship to Okello and invited him to Kampala where they happily shook hands as they posed for photographs. Opio’s research shows that between 1971 and 1972, Amin met Okello twice and in each meeting, he offered Okello a position in his government.

At first Opio says he offered him a ministerial post and when he declined it, he again proposed to him the vice presidency.

Interestingly, in the second discussion, Opio writes that Okello audaciously told Amin that let him be the president and he (Amin) his deputy since he already had experience in leading a government in Zanzibar, something that Amin could not offer. Thus it apparently became clear that the two men could not work together, hence a new phase of relationship developed.

Since Amin could not bring Okello inside his government and control him from within, he kept a close eye on him. From then on, Amin’s intelligence service intensified its watch over Okello. For Okello, he started a plan to fight Amin and his home soon became a meeting point for anti-Amin plotters.

Opio states that Okello-anti Amin’s plot became serious that in early 1973 it had both local and regional wings based in Ethiopia where young men were being recruited and sent for training.

Arrest and execution

On September 6, 1973, Okello told his family members that he was travelling to Kampala to buy building materials, but instead, he went to his brother’s home in Amugo, a neighbouring sub-county.

Just after he left, a heavily armed squad from the Sate Research Bureau stormed his home. When they couldn’t locate him, they proceeded to Amugo.

The executioners drove into the compound of Okello’s relative. In an instant, Opio says Amin’s acolytes surrounded him before pouncing on him, handcuffed and bundled him onto their truck and drove off.

Eye witnesses say as the truck drove through Ogowie Trading Centre, Okello stretched out his head through the truck and shouted: “I am Field Marshal Okello en dong Omaka oko, kobi ijo ipaco ni an dong awoto oko” (I am Field Marshal Okello under abduction, say goodbye to my family).

It was the last time the Zanzibar revolution icon was seen.