This girl (call her Dinnah) is one of the two akauntas at this neighbourhood bar you like because the management listens when they’re asked to reduce the music volume.

Dinnah has revealed to you this is her second month in Dar. You’ve somewhat opened up to her, and she has reciprocated by being open to you.

“I’m very strict with myself… I’m here in Dar to make money, so I can’t allow anyone to mess with me because if I do, I’ll lose direction,” Dinnah says to you, out of the blue, for you’ve not asked her any question to attract this assertion. Or maybe you have but can’t remember. Senility!

You feel like asking her what she means by “not allowing anyone to mess with her” or how any messing, whatever that means, would impede her determination to make money. Kutengeneza hela, in her own words.

You toss to her another intrusive question: “Do you have a child back at home?”

“No; I don’t have one yet—I’ll only bear children after getting married,” she says, adding, “Right now, I want to focus on making money.” Dinnah and money-making ambition!

I tell her I agree that’s important. Everybody needs to focus on making money, no matter what sector of the economy they are in.

You too, son of Muyanza, you say to yourself, are focused on making money by wearing your fingers on the computer keyboard most of your life. You’ve ended up with nothing, of course, but so what? Everyone has their own kind of luck. Kila mtu na bahati yake, we say in Kiswahili.

You’re a career scribe, and so you’re entitled to ask questions even on matters that don’t concern you, aren’t you? So, you ask Dinnah whether she has a boyfriend.

“Me, a boyfriend? No!” she says emphatically. When you ask how come a beautiful girl such as her is without a boyfriend, she quickly says she has a partner.

“I’ve got someone—not a boyfriend as such, but a partner—he’s like a husband to me,” she explains.

“It means…you stay together?” you ask.

“Nope, he doesn’t live in Dar… He’s in Arusha,” she says.

“Oho!” you remark, “so, how are you relating? Yaani, your husband lives in Arusha, and you work and live in Dar. How?” you query.

“There’s no problem… We manage,” she says and adds, “when there’s a need for him and I to be together, he sends me a fare, and I travel to Arusha by any of these nighttime buses.”

You ask if her Arusha man is living single the way she is in Dar.

She says no; he’s married to some other woman there, but that’s not a problem.

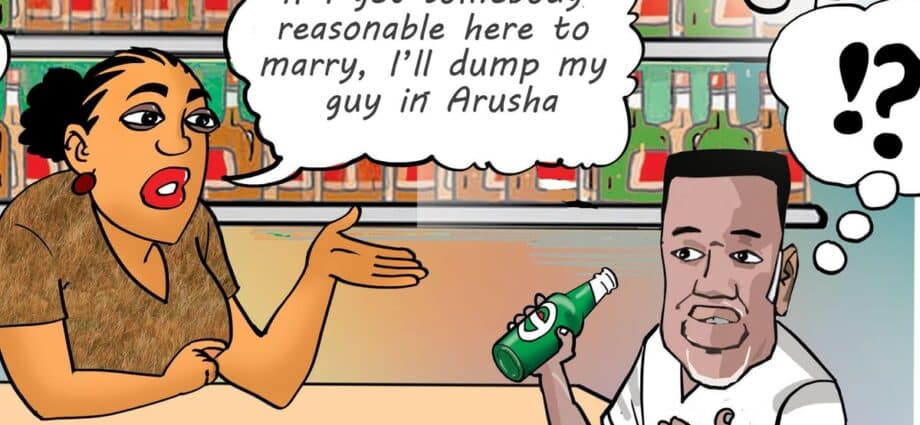

“I’m not dedicated to him by a hundred percent, so if I get somebody reasonable here in Dar to marry me, I’ll dump him,” she says, wearing a face that shows she surely means what she’s saying.

You’re somewhat confused by this assertion. Which is why, without further ado, you pay for the three “Castro Laiti” you’ve swallowed plus two sodas for Dinnah and bid her goodnight.

This girl (call her Dinnah) is one of the two akauntas at this neighbourhood bar you like because the management listens when they’re asked to reduce the music volume.

Dinnah has revealed to you this is her second month in Dar. You’ve somewhat opened up to her, and she has reciprocated by being open to you.

“I’m very strict with myself… I’m here in Dar to make money, so I can’t allow anyone to mess with me because if I do, I’ll lose direction,” Dinnah says to you, out of the blue, for you’ve not asked her any question to attract this assertion. Or maybe you have but can’t remember. Senility!

You feel like asking her what she means by “not allowing anyone to mess with her” or how any messing, whatever that means, would impede her determination to make money. Kutengeneza hela, in her own words.

You toss to her another intrusive question: “Do you have a child back at home?”

“No; I don’t have one yet—I’ll only bear children after getting married,” she says, adding, “Right now, I want to focus on making money.” Dinnah and money-making ambition!

I tell her I agree that’s important. Everybody needs to focus on making money, no matter what sector of the economy they are in.

You too, son of Muyanza, you say to yourself, are focused on making money by wearing your fingers on the computer keyboard most of your life. You’ve ended up with nothing, of course, but so what? Everyone has their own kind of luck. Kila mtu na bahati yake, we say in Kiswahili.

You’re a career scribe, and so you’re entitled to ask questions even on matters that don’t concern you, aren’t you? So, you ask Dinnah whether she has a boyfriend.

“Me, a boyfriend? No!” she says emphatically. When you ask how come a beautiful girl such as her is without a boyfriend, she quickly says she has a partner.

“I’ve got someone—not a boyfriend as such, but a partner—he’s like a husband to me,” she explains.

“It means…you stay together?” you ask.

“Nope, he doesn’t live in Dar… He’s in Arusha,” she says.

“Oho!” you remark, “so, how are you relating? Yaani, your husband lives in Arusha, and you work and live in Dar. How?” you query.

“There’s no problem… We manage,” she says and adds, “when there’s a need for him and I to be together, he sends me a fare, and I travel to Arusha by any of these nighttime buses.”

You ask if her Arusha man is living single the way she is in Dar.

She says no; he’s married to some other woman there, but that’s not a problem.

“I’m not dedicated to him by a hundred percent, so if I get somebody reasonable here in Dar to marry me, I’ll dump him,” she says, wearing a face that shows she surely means what she’s saying.

You’re somewhat confused by this assertion. Which is why, without further ado, you pay for the three “Castro Laiti” you’ve swallowed plus two sodas for Dinnah and bid her goodnight.