Arusha. A journey from Arusha to Terrat ward in Tanzania’s Simanjiro district reveals a harsh reality for pastoral communities. Dust devils dance across rough, unpaved roads, stretching the 84-kilometre trip to two and a half hours.

Here, livestock keeping is the lifeblood of the community, practiced by 80 percent of the population, primarily Maasai people.

However, a troubling sight disrupts the traditional savanna landscape: thriving invasive weeds. Local host Joshua Laizer identifies them as Parthenium (gugu karoti in Maasai), a species notorious for its rapid spread and inedibility by livestock.

“No animals are grazing these plants. Rather, they dispersed far and quickly,” Mr Laizer explained, highlighting the significant problem posed by this species despite many invasive plants.

At Terrat village, Mr Leboy Ngoira, a middle-aged livestock keeper, paints a grim picture. His large cattle enclosure, meant for over 500 animals, holds less than 100. He blames the decline on shrinking grazing lands due to drought and invasive weeds.

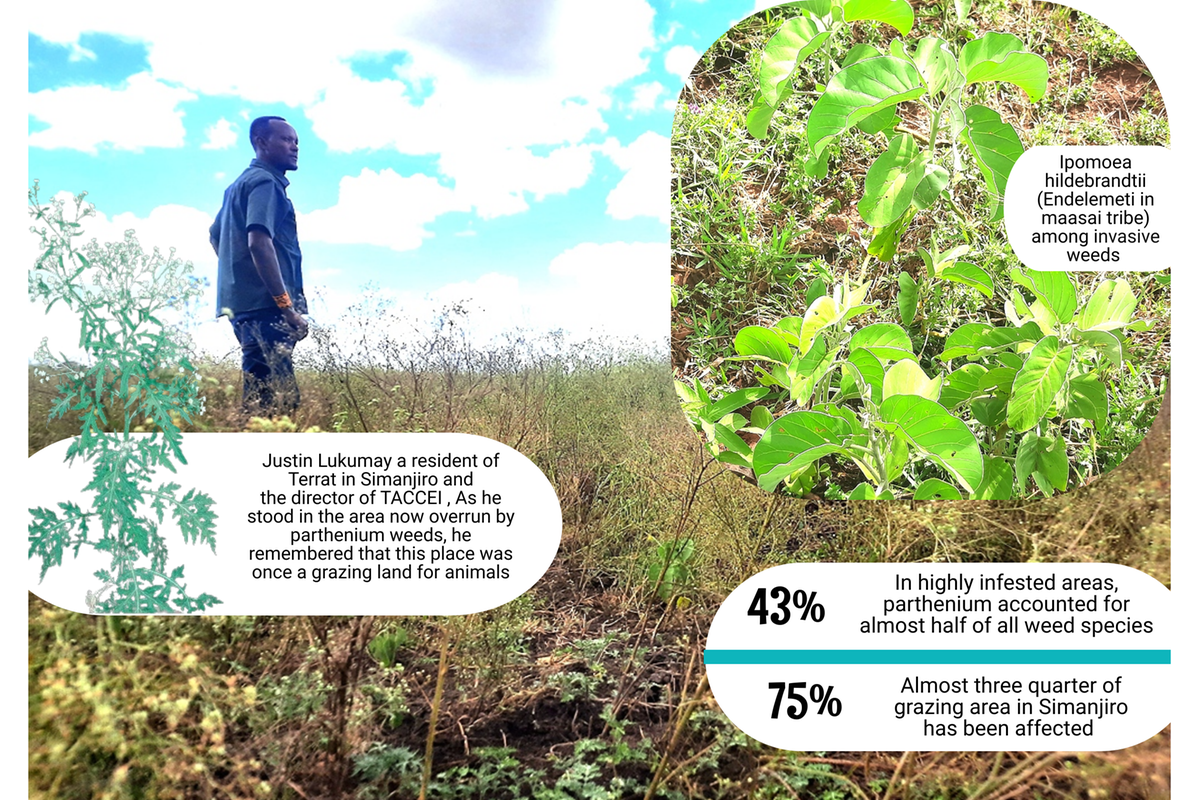

“Currently, we don’t keep many cows. We have gained knowledge on raising a few for efficiency and proper care,” Mr Ngoira stated. He further explained that the reduction in livestock numbers is due to the diminishing grazing lands affected by drought and the invasion of inedible weeds such as Ipomoea hildebrandtii (Endelemeti in Maasai) and Parthenium.

In another compound, Mr Lesira Samburi, an elderly traditional leader (Laigwanani) of the tribe, also discussed the invasive species issue.

“Cattle don’t eat them, and because these weeds are mixed with others, they might accidentally consume them. When they do, they sometimes fall ill and produce bitter milk that is unusable,” Mr Samburi explained.

A study, “Parthenium hysterophorus L. (Asteraceae) in Sub-Saharan Africa, 2013,” noted that Parthenium, commonly known as parthenium weed or famine weed, is a highly invasive annual herbaceous plant native to the Americas, specifically Mexico and the southwestern United States.

“It has spread to many parts of the world, becoming a significant weed in agricultural areas, pastures, and natural habitats. Highly invasive and aggressive, capable of colonising a wide range of habitats and native vegetation,” noted the study.

The study noted that controlling it is challenging due to its prolific seed production, rapid spread, and ability to tolerate a wide range of environmental conditions.

According to the Tanzania Plant Health and Pesticides Authority (TPHPA), Parthenium was first observed in 2010 in Arusha Region and later spread to the regions of Manyara, Kilimanjaro, Kagera, and Geita. According to them, the weeds have invaded both farming areas, grazing areas, and wildlife habitats and proved to be a significant problem in those areas.

How big is the problem?

The 2022 population census indicated that Simanjiro is home to 291,169 people spread across 18 wards. The district is located in a semi-arid area, receiving average rainfall between 400 and 500 millimetres per year. This climate condition is conducive to the proliferation of invasive weeds.

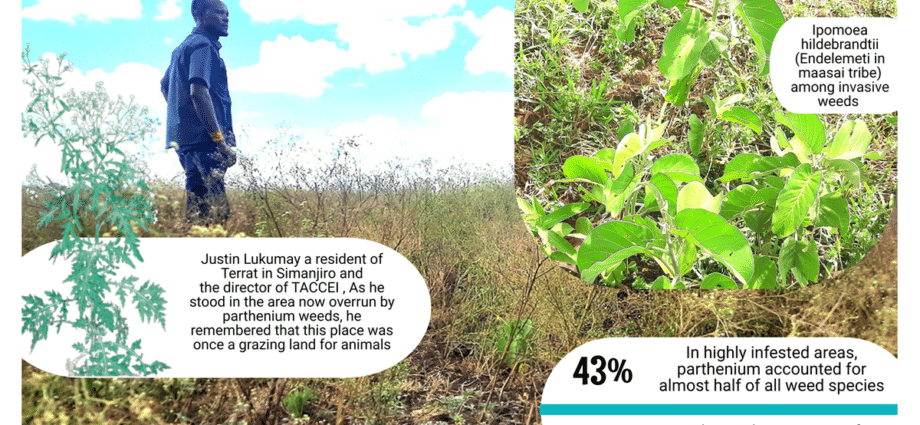

In Terrat ward, at some point, we travelled for up to 10 minutes without seeing any other vegetation in the savanna, which used to serve as grazing land, according to Justin Robert Lukumay, a resident of the area. At certain points, we had to stop to observe how extensively the grass had grown in large areas.

For a person of five or six feet in height, the grass can reach from the knees to the waist and has flourished significantly. “We used to graze here when we were young,” said Justin, who is also the director of a non-profit organisation named Tanzania Conservation and Community Empowerment Initiative (TACCEI) based in Simanjiro.

A study titled “Effects of the Abundance of Parthenium Weed on the Composition and Diversity of Other Herbaceous Plant Species in Simanjiro Rangeland,” conducted by five scholars from Tanzania and Kenya in 2022, found that “parthenium is the most dominant weed and hurts the diversity and composition of native herbaceous plant species.”

The study documented grass species in areas with high, low, and no infestation of parthenium and concluded that in highly infested areas, the weed accounted for 43 percent of all species, with the highest percentage of another species, Eleusine indica, recorded at 25 percent. In areas with a low infestation, the plant dominated at 36.2 percent, followed by 7.9 percent of other species. In non-infested areas, there was no parthenium, but another invasive weed, Ipomea hildebrandtii, accounted for 3.7 percent of grass species.

Simanjiro District Livestock Officer, Dastan Mdolwa, states that nearly a quarter of the land in the district has been invaded by the invasive plant. “It started gradually in the village of Terrat, but now it has spread to almost three-quarters of the entire district,” Mdolwa said.

Chairman of the Parthenium Weed Committee in Arusha, Ndelekwa Kaaya, said: “The longer we delay, the more it spreads… wherever it grows, the vegetation in that area is affected, and one can get up to less than 30 percent of what they would otherwise harvest.”

Mr Kaaya added that the plant has spread to many areas in the region and other parts of the country. During my field visit to Monduli District in Arusha Region, I also observed these weeds, although not as extensively as in Simanjiro.

Monduli is among the driest districts. It features a warm climate at low elevations and a chilly climate at high elevations, with rainfall ranging from less than 500 millimetres to 900. The district’s residents engage in various economic activities, including livestock husbandry, agriculture, and wildlife conservation. The district has a population of 227,585, with over 90 percent actively involved in these activities.

“In the past, these plants were not present, but this year, some areas have seen rapid growth,” said Mr Yamati Laizer, chairman of Losirwa village in Esilalei Ward, Monduli District, speaking about the invasive plants. Mr Yamati mentioned that this situation has led to some areas losing grazing land and agricultural plots.

What are they doing?

The chairman of Terrat Village, Kone Dedukenya, stated that they have decided to set aside grazing areas and protect them. “Last year, in collaboration with the council, they allocated areas for us that we had designated, and people are not allowed to graze there,” he said.

In one area we visited, it was surrounded by wire fences. The area covers 160,000 square metres (around 40 acres), according to the Grazing Committee Supervisor for Terrat, Stephano Kabuni. The area doesn’t seem to have abundant grass, but it’s better compared to just outside the fence.

“We removed all the invasive weeds and planted native grass,” Mr Kabuni said, adding that there are four other similar areas designated for research purposes.

Speaking about the history of invasive weeds, he said that since 2019, in an area of 715 acres, they have removed the invasive weed Ipomoea hildebrandtii but failed to control Parthenium. “When you remove that thing (Parthenium), its seeds, whether fresh or dried, will thrive. We have failed to control it,” he said.

At Losirwa village in Monduli, they have also set aside grazing areas, but unlike Terrat, there, the grass seems to thrive. Yamati said in his village, there are 12 women’s groups involved in activities such as planting grass and other activities to improve their economic situation and reduce dependency.

The leader of one of the women’s groups consisting of 30 pastoralist women, Ms Grace Narumuta, said they received training on how to plant and care for grass in early 2023.

“We were educated by the Pastoral Women’s Council (PWC) and succeeded in planting grass, which, as you can see, has thrived. On International Women’s Day, we harvested seeds and sold them to other groups,” Ms Grace said, adding that these areas have been controlled and there are no invasive plants. Ms Grace says now they make money, and they move away from hazardous activities to the environment, such as selling charcoal and firewood.

PWC project manager for Monduli, Stella James, said: “We women in these communities have been left behind, so recognising this, our organisation saw the importance of assisting women to reduce dependency. We have assisted them in many issues; among them is planting grazed plants.”

Solution and Government say

A study on “Parthenium hysterophorus” suggested that “integrated weed management approaches combining cultural, mechanical, chemical, and biological control methods are often employed to manage parthenium infestations.”

Chairman Kaaya said they are now educating people about the weed and suggested that the solution is uprooting and carefully burning it.

Researcher of plant pests from the government authority TPHPA, Ramadhan Kilewa, says they have adopted Integrated Pest Management (IPM) in controlling these pests, including the biological method of using specific insects that feed only on parthenium without affecting other plants.

The expert added: “Methods of uprooting the affected plants and burning them are also used, and others include special chemicals used to eradicate the plant without harming other vegetation.”

However, he admits that all these methods depend on the type of area, specifying that you cannot use chemical methods in grazing areas or wildlife reserves because if the animals eat the poisonous plants, they will die, but the biological method is a solution for such areas.

TPHPA continues to distribute and provide education in affected areas, and the expert acknowledges that these solutions bring hope.

When asked about the issue, Simanjiro District Commissioner Faki Lulandala said they are continuing efforts to address the issue of parthenium weed, diligently seeking a permanent solution.

Supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation